The previous work got me thinking. The LMO problem was, apparently, flaky rivets at the RCA connector; I peened those and the instability went away completely. The scratchy noise in the audio was fixed by generous application of desoldering braid and fresh solder on the audio board. And, whereas I was seeing only a few mV of RF at the output side of T1 (the balanced modulator output transformer), after again re-soldering a few points I’ve suddenly got close to the expected level – about 260 mV peak. No real explanation for why it suddenly jumped from 25 to over 250 mV. All of this points to bad connections and oxidization.

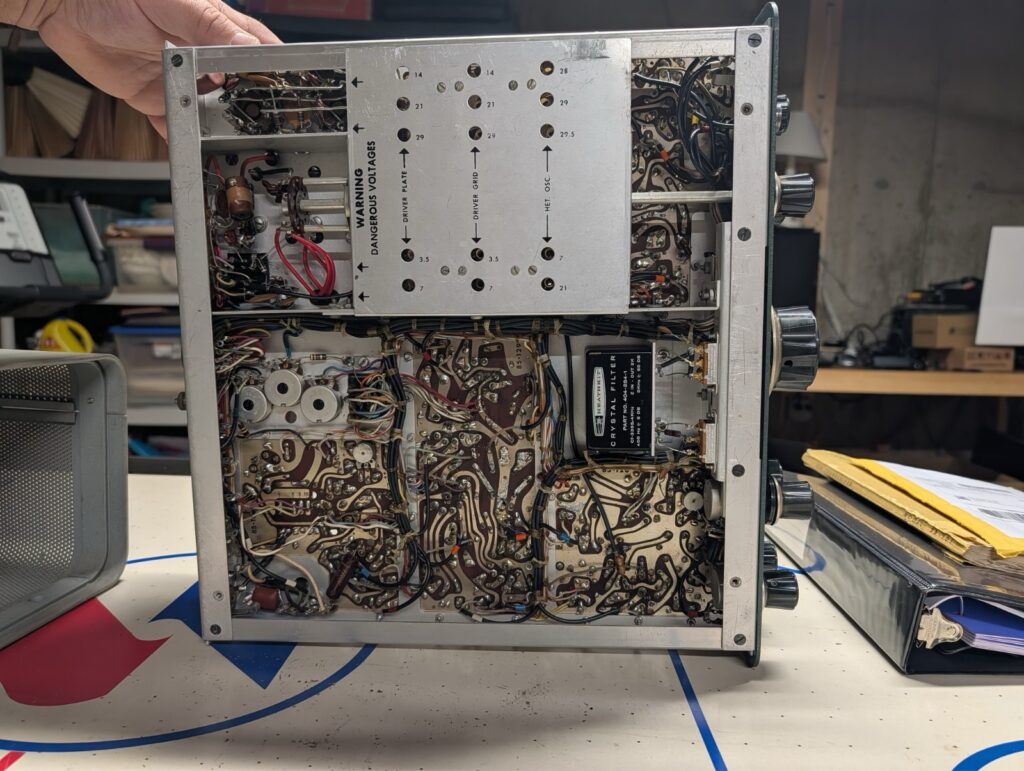

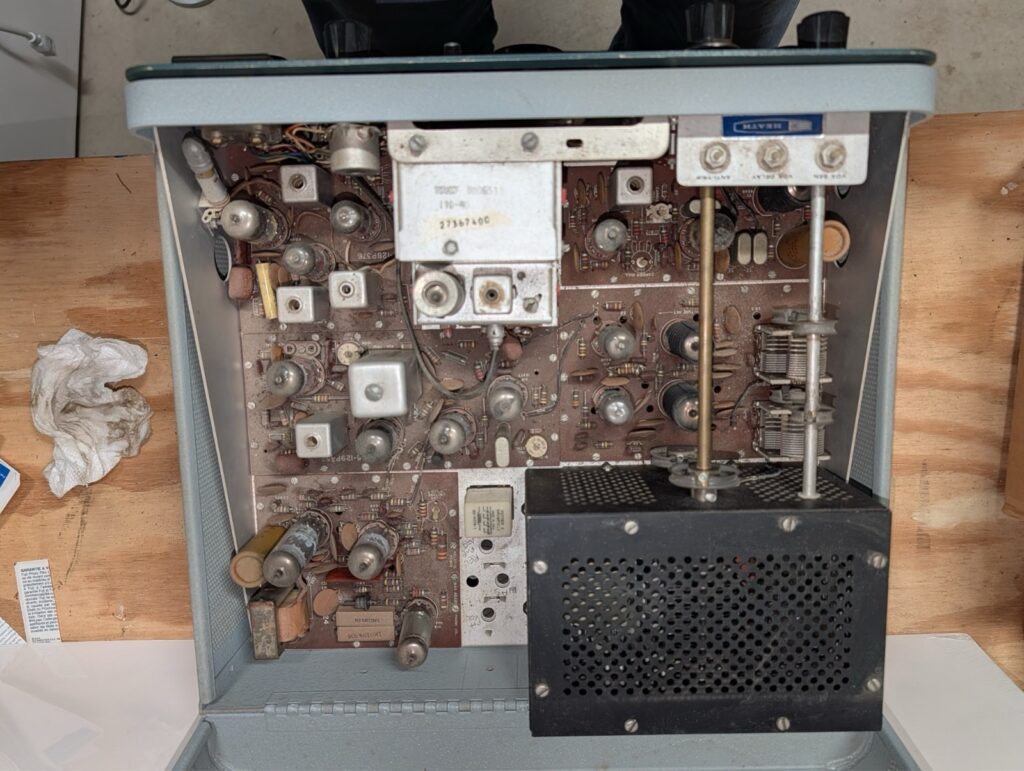

Now onward. V3 is not amplifying as it should. I get about 150-175 mV peak RF out of pin 5 (the plate) where it should be around 7 V. I swapped V3 with V4, then V2 & V3 with V10 & V11, since they are all the same 6AU6 type. Of course that didn’t make a difference. I’m not expecting to find bad tubes. What I suspect is happening is that there is old flux contaminating a number of solder joints. After sitting idle for decades, there is now oxidization that is getting disturbed by heat and motion. That’s causing these marginal or bad solder joints to rather randomly manifest themselves. The solder joints all look OK; most are not terribly pretty, as I would expect with a Heathkit, but solid. It’s telling, though, that de- and re-soldering is fixing so many issues. I decided to simply go through and de-solder, thoroughly clean, and properly re-solder every joint I could get to on the IF, bandpass, and driver boards.

I also had a very flaky meter zero potentiometer, and if it’s bad then the carrier null is probably not far behind. Of course you can’t buy direct replacements for the originals, so I bought some new top-adjust 10 turn trim pots. One of them fixed the meter zero issue quite nicely, and I’ll replace the carrier null pot when I have time.

Unfortunately none of the work I have done has had the slightest impact on the RF output. It’s still next to nothing. About 1W or less on 80 meters, and maybe 10 or 12 on 10 meters. I’ve asked advice on the Heathkit radios group (here) and and working with a couple of guys who understand tube circuits better than I do to troubleshoot.